Note pour le lecteur : Entre le moment où je découvre cette exposition et celui où je publie cet article, treize mois se sont écoulés. Quelle année! Et pourtant, à travers les multiples turbulences, les visages, les dessins et la pensée de Netta n’ont cessé de m’accompagner.

Si je choisis de publier cette interview aujourd’hui, c’est parce que, malgré tout : les guerres, la faim, le désespoir, la violence, je crois qu’elle a encore quelque chose à nous dire, à nous demander.

Peut-être maintenant, plus que jamais.

L’article et l’interview sont en anglais afin de rester fidèle à notre conversation. L’exposition “Shattered Hopes & Roads Not Taken” s’est tenue au Musée de Tel Aviv de mars à décembre 2024.

Did you ever wonder at what point in your journey is your history made?

Is it forged when we take the expected main avenue or when we dare to wander down an unfamiliar dark alley? Perhaps it is born in our failures: the wrong turns, the sour love stories, the five years detour, the unsuccessful job applications, the bus we missed that nevertheless led us to meeting new travel companions. Maybe that’s how our history is drawn.

How my life would have turned out, had I remained living in Brussels after college ? Would I be alive, would I be myself, had my mother never returned from Israel in 1985? What my life would have become had I been accepted into that school ? Where would I be, had I not stepped into that bar at that precise moment last year? Would destiny have found me anyway?

These questions echo the infinite possibilities we are the outcome from. Netta Lieber Sheffer, the artist I had the chance to meet for this third episode, explores this questioning on a much broader scale: that of an entire country.

The artist in her studio, December 2024, Tel Aviv

In her first solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Shattered Hopes & Roads Not Taken, Netta emerges as both an archaeologist and a farmer, tilling the rich, complex soil of Israel’s past. She digs, turns, and returns the earth, delving through layers of remembrance and oblivion in search of long-buried roots.

She asks: How did we get here?

It is as if we were finding ourselves on a fast-lane highway towards destruction without grasping fully the origins of its twists. What moves, what chance, what changes brought us to this very point ? And where will those choices lead us next ?

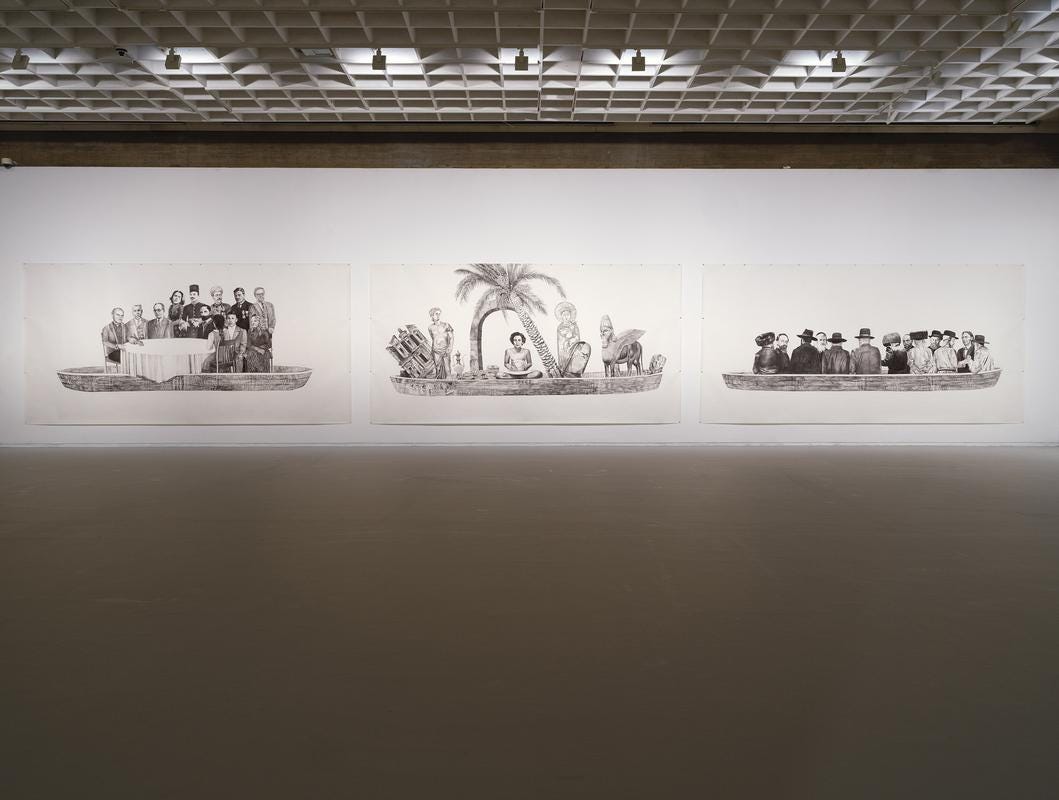

To guide us through the labyrinth of history, Netta employs the motif of unanchored boats, floating on the large white walls of the Museum as if they seem to endlessly search for their ultimate destination. While some of our history is grounded into Earth – much like the trees we plant and the houses we build – other parts drift free, holding on to anecdotes and imaginaries we have been repeating ourselves about ourselves, for generations.

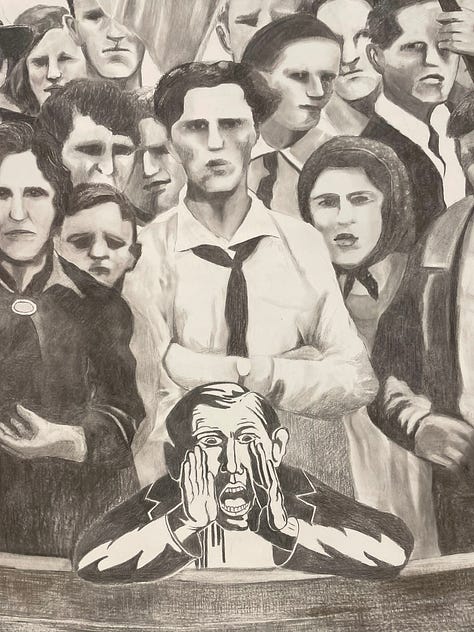

Each boat, eleven in total, carries people who themselves carry ideas and visions of what Zionism once meant. Zi-o-nism. A three-syllable word which has become totally unpronounceable in today’s world as it is being associated with the worst atrocities committed by humans to other humans. While debates rage across world media over its meaning, we are compelled to pause for a moment and ask ourselves a far more essential question:

Which zionism are we actually talking about?

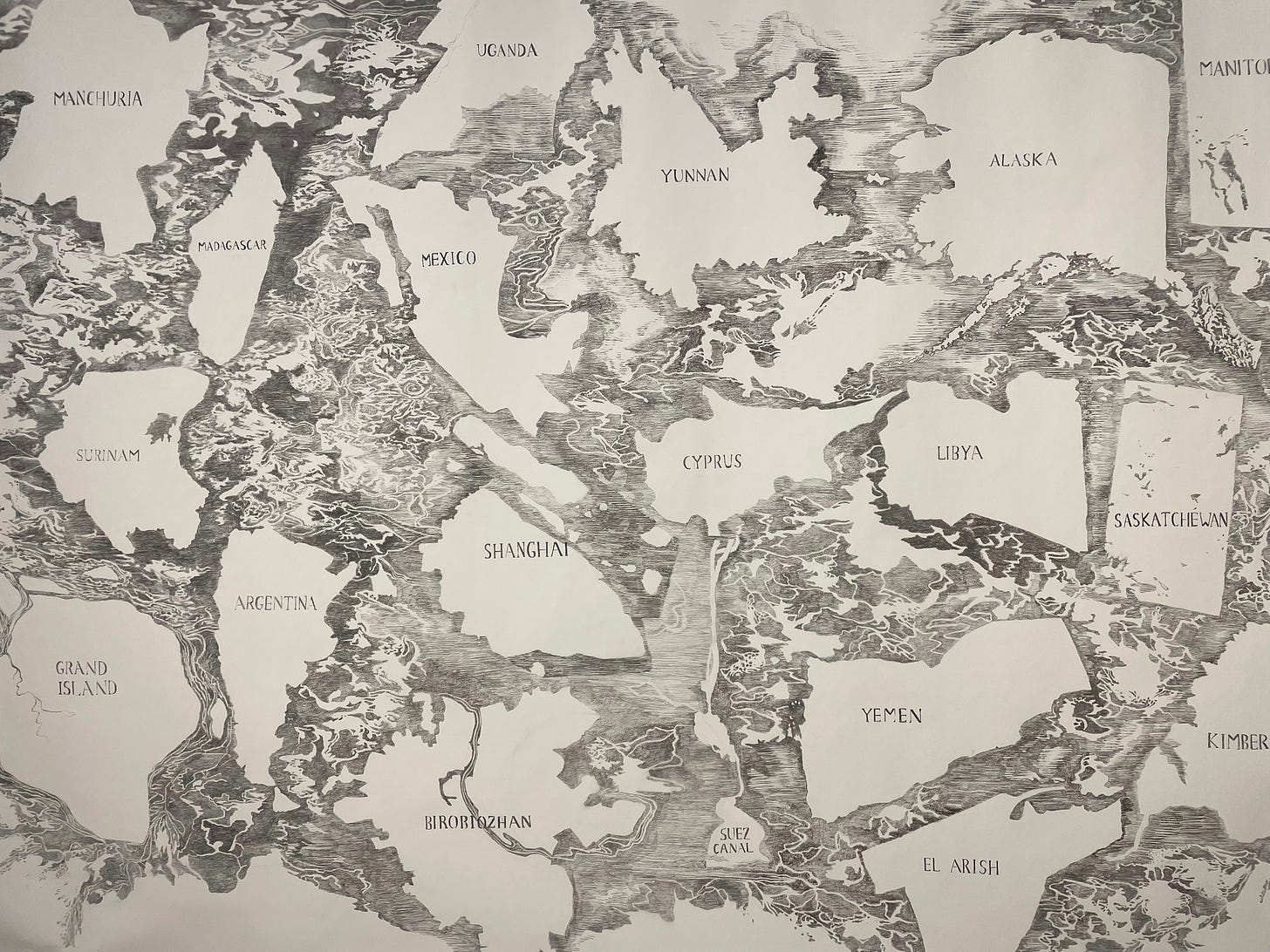

On this map, after researching more than 40 historical proposals, Netta Lieber Sheffer drew 26 Territorial Alternatives — each imagined, designed, or advocated as a potential Jewish homeland before the founding of Israel in 1948.

So, how did we get here?

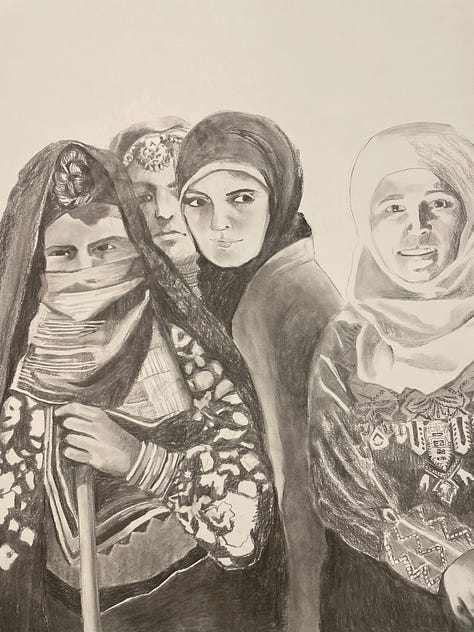

Imagine, if you will, being Esther Moyal, aboard the boat of Arab jews; lebanese writer and activist, born in 1874, she fought for what some would call an “idealistic vision”: Zionism as a space that could embrace peacefully her dual identity of being both Arab and Jewish. Imagine, if you will, being Regina Danon, one of the early gynaecologist who saw in Zionism a space for women’s emancipation, pioneering a new social order of gender-equity. It’s definitely the feeling we get visiting Ayanot, where the artist has been living and practicing for eighteen years, and which used to be a working farm led by, lived by and managed by women only. Meshek Poalot, a revolution in itself.

Or think of Rabbi Joel Teitelbaum, alarmist thinker, worried preacher, warning the communities of Eastern Europe that Zionism would spell the end of Judaism; while figures like R.Binyamin and Martin Buber saw Zionism as a one-life-opportunity to reshape a complex interplay between land, nation, and religion.

In what chamber of our collective memory are these figures buried today ? What fragments of these shattered hopes and roads not taken remain in our unconscious collective body ? Do we live in continuity, reaction, or rupture to them ? How can we build a durable future without confronting the roads we did not take, the intersections we passed by, without realizing?

Arab-Jews boat, The Levantine option boat, Metaphysical exile boat

The artist between the Metaphysical exile boat and the Female leadership boat. Netta works on monumental charcoal drawings, a medium that itself seems to hold the memory of time and fragility: wood transformed into carbon, laid down on paper.

Each raft in Netta’s exhibition carries not just a history, a movement or an idea – but also a sense of isolation and divergence. As if Zionism could very well be all of these. But not together, and not at the same time. How realistic is it to build a single collective narrative in this constant fragmented flux ?

Where the world would have us choose simplistic static narratives, pros or against, zionists and anti, victims and persecutors, Netta invites us to sit with the entanglements of history, to look back and trace the infinite web of destinies, the stories which shaped the story of Israel, as it has become, today.

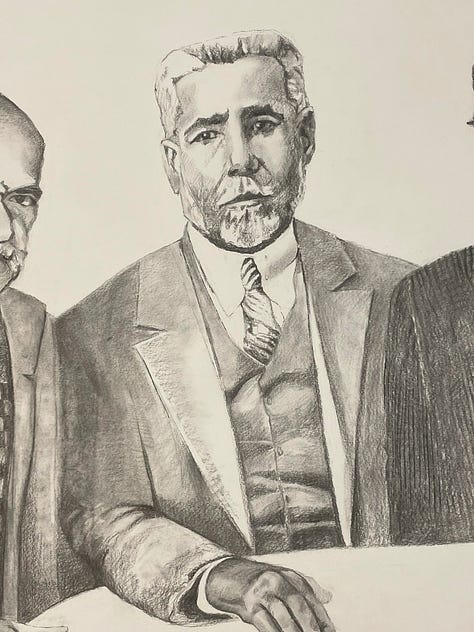

Detailed figures from the boats, Museum of Tel Aviv, December 2024

If Netta’s exhibition moves me so deeply, it’s because the multitudes she presents, I carry them within me.

And these days, I keep wondering: How did I get here?

As I walked through the exhibition, I couldn’t help but think of those who are so vividly present in my life by virtue of their absence. In a quiet moment, I catch the serene face of my great-grandfather, Moïse Silberring, a Belarusian refugee and bundist—a member of the jewish socialist, anti-zionist movement whose motto was: “Wherever I live, that is my homeland.” Plante-toi et tu pousseras. I also seek the trace of my great-grandmother, Fanny Faigenbaum, born in Al Kuds (Palestine) in 1913, who narrowly escaped the death camps by declaring herself a Turkish citizen. I confront the memories of my days spent in the youth movement Hashomer Hatzair, where Israel was painted as a dream of agriculture and communal hope. I recall my time at the School of Oriental and African Studies, in London, where postcolonial studies, Edward Said’s Orientalism, and the struggles of my Saudi, Jordanian, Lebanese, and Egyptian friends – all grandchildren of displaced Palestinians – wove together a renewed narrative of exile and identity. And finally, through the Metaphysical Exile Boat, I think of the study of the Torah, the depth of its wisdom, the violence of its words, all part of the enduring myth of a people’s return to its Promised Land.

Netta Lieber Sheffer revealed me to myself: these infinite possibilities are already within me.

I am this soil. Perforated by both remembrance and oblivion, shaped by choices made and paths abandoned.

Fanny Faigenbaum, my paternal great-grandmother. Her story remains to be fully uncovered. A German Jew, born in Al-Quds in 1913. Polyglot, educated, divorced, witty. In this photo, she wears a pin with the Turkish flag – a detail that likely saved her and my grandfather from the Malines transit camp in 1942.

If I decide to finally publish this article now, it is because these days, I feel a bit like one of those boats: filled with ideas and stories, yet without an anchor, on my way towards a future that looks both wonderfully open and overwhelmingly vague, navigating turbulent waves through a tense historical moment, from Geneva to Tel Aviv, via Brussels.

The other night, I was having dinner with my brother and my cousin when my brother said: “There’s no point in saying I should have, I could have. What purpose does it serve? There is nothing you can do about it anymore.” I thought of Netta and the value of looking back. Not as some sort of nostalgic exercise, but as something more deliberate, more constructive. Like the farmer turning and digging through the layers of earth in order to rejuvenate the soil, to renew life.

It is through artists like Netta, through the work of thinkers and historians, that these buried traces endure. We look back to remember.

What we are.

Who we could have been.

And decide what we might still become.

I thank Netta personally for bringing these questions in front of my eyes at a time I most needed it, and for trusting me with this interview.

*

Enjoy the Dialogue.

Thank you for your reading 🙏

Don’t hesitate to share this Newsletter with someone who could appreciate it.